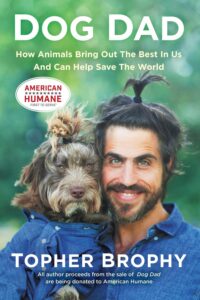

The memoir Dog Dad chronicles its author’s transformation from a lonely young man searching desperately for a sense of purpose in travel and obsessive exercise to a “dog dad” who discovers that he can finally feel love and connection through a relationship with his canine charge, Rosenberg, to whom he bears a striking resemblance.

That author—whose nom de plume and Instagram is Topher Brophy—is most famous for posing with said dog in matching outfits, dressed and photographed by his wife, Chantal Adair, who goes by “The Dog Styler.” This pursuit has brought them 210,000 Instagram followers and media coverage from CBS, Cosmopolitan, and People. Brophy has used this platform to support organizations like Doctors Without Borders, the National Resources Defense Council, and the UN Refugee Agency.

Dog Dad is set for release in September, and Brophy will donate its profits to American Humane. Now also a father to two human children and one additional dog, he spoke to The Farmer’s Dog about how his family has changed as it’s grown, how he looks out for Rosenberg while making content for social media, and why he prefers to call dogs “animal companions” rather than “pets.”

You’ve mentioned not wanting to call dogs “pets.” When I think of a “pet,” I think of an animal whose place in a human’s life is companionship—and, while calling them that word, you can certainly love them or regard them as family. I know it’s semantics, but what’s your objection to that word?

I want to be clear, I don’t want to cancel the word “pet.” And I don’t want to shame anybody, either. I’m anti-shaming and anti- any of those things that make people feel bad about anything they do—unless, obviously, it’s hurting other people. I don’t want to attack that word. I just feel that words do matter, and the word “pet” does not give respect to all that animals do for us—especially ones that we’re close to. Looking back in history to 30,000-plus years ago, when we evolved with dogs, they helped us survive—they helped us hunt as partners. They were security systems. They were transportation. We might not be here without them.

Now they provide so much more. They emotionally support us in ways we can’t even understand by helping us extract our empathy and our innocence, helping us remain present in the moment. They’re companions. A “pet” is something that’s a little patronizing, and I think dogs don’t deserve to be patronized in any way—which is why I so encourage “animal child,” “animal companion,” “animal sibling,” and all these other words that I think help us interact with them and respect them, treat them better as a whole.

Now they provide so much more. They emotionally support us in ways we can’t even understand by helping us extract our empathy and our innocence, helping us remain present in the moment. They’re companions. A “pet” is something that’s a little patronizing, and I think dogs don’t deserve to be patronized in any way—which is why I so encourage “animal child,” “animal companion,” “animal sibling,” and all these other words that I think help us interact with them and respect them, treat them better as a whole.

What work goes into conceiving and executing each post?

It’s a process between me and my wife—who, when I first met her, was a photographer I was working with that specialized in human and animal photography. She was an ex-fashion photographer. She’s the artistic brains behind the operation, just to be very clear. It’s Chantal Adair, who goes by The Dog Styler. She’s the creative force. I’m the man who coincidentally looks like his puppy, so to speak. But we do collaborate on ideas.

How do you make sure that Rosenberg is comfortable during a shoot?

First and foremost, the temperature is important. Dogs have built-in fur coats—so if the environment is hot, its not good for him to wear clothes. So we’ll avoid any time the temperature in any place is too hot.

So no shoots today.

Exactly. Definitely not. Unless it’s indoors with a lot of AC, but there’s no plan.

I think the other thing is clothes that are not too constricting or too tight. That’s not going to be good for a pup. It’s got to fit his body properly. It has to be either the perfect fit naturally or customized to fit a dog’s body, which is not like a human’s, even a small human’s.

From when Rosenberg was very young, we’ve had this symbiotic bond where he wants to be so close around me and to be held. He’s the type of pup who will follow me wherever I go in the house and want to be near me.

He also has a bunch of anxiety, so in a way the clothes can act sometimes as a thunder vest of sorts—where I think it might ease a little anxiety in him. Most dogs aren’t like that, and if he didn’t naturally like doing the process we wouldn’t do it.

He’s such a professional. He will always gravitate toward a camera if he sees it. Part of it might be that when he was a pup he got used to it, and he liked the habit of the behavior and its comfort. It’s very possible. But being the center of attention makes him happy. And it’s something that we do kind of ritually where the pack is together, which is the most important thing for him as a family guy.

In your book, you mention not wanting to be a person who gives less attention to your dog after having human children. How has your relationship with Rosenberg changed as your family has grown?

A lot of people have said to us, “Wait, wait, wait—you’re going to have human children, and you’re going to start paying less attention to your animal children.” I hear a lot of horror stories of people neglecting their animal kids when they have human kids, and it’s so heartbreaking.

It really wasn’t that way for us at all. It was an enhancement to see the children interact together. And Rosenberg was present at the birth of our first human child, Topper. To him, it was all normal. We have a photo of them together in the hospital, which is one of my favorite photos we’ve ever taken together, where Rosenberg and I are in doctors’ outfits—which is just part of the kitsch.

Watching Rosenberg and Topper together was one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever experienced. As humans, we have a predisposition to love dogs. It’s something I mentioned before—in 30,000 years of evolution, we’ve been conditioned to love each other. So that’s why, when humans see a dog, they smile. It’s one of the things that’s baked into our DNA.

But when we had a human child, we got them together and they loved each other—and we watched it closely at first because we want to make sure that everybody gets along, and it’s a complete enhancement. Rosenberg has been his best friend since the moment Topper was born, and the same principle applied to our second human child, and the same thing applied to our second dog, our fourth child, Heaven—when she was a puppy, all she knew was her human sister, her human brother, and then her animal brother, Rosenberg.

From @TopherBrophy on Instagram. Photo: @TheDogStyler

But it seems that was a challenge at first; in the book, you describe Rosenberg’s initial attitude toward Heaven as a “demonic bloodlust.”

Thanks for reminding me, because sometimes I put it out of my brain. It was so difficult. It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do in my life.

Man, was that heartbreaking—because Rosenberg just did not accept Heaven when she came into our lives, and we had this harmonious family. The enhancement of humans and Rosenberg together. He accepted them instantly. I watched Rosenberg protect his siblings, his brother—he was so loving and wanted to be around all the time, and he kind of guarded his room. He was his protector. And to me it was a concrete example of the bond humans and dogs have innately. But there are challenges, to your point. When Heaven came into our lives, Rosenberg didn’t accept her. It took about an entire year before he accepted her in the house as part of the pack. It was really discouraging, and it was emotionally devastating for us at the time.

From @TopherBrophy on Instagram. Photo: @TheDogStyler

What makes Rosenberg happy off-camera?

He loves to run as fast as any dog can run. He’s got zoomies all the time. And he loves to snuggle close to me and his mom and all his siblings—the two humans. And they had such a rocky start, but now that Rosenberg has accepted Heaven into the pack they have a beautiful relationship. They’re always together. They sleep on top of each other. They constantly feed off of each other’s energy and have fun and play together. So playing with his sister is a huge part of his life now, which is beautiful and makes me forget the year of pain where he did not accept her. He really just loves being with us and being close to us. It’s the most important thing. He loves the family, loves the pack, and also helps us all be together as much as possible—because we know he’s only happy when we’re all together.

Rosenberg is really introspective. I have this theory that there are dog cats and cat dogs. And my first animal in my life that really helped me understand that, even though I didn’t fit properly in the world, everything was going to be okay, gave me that love, was a cat—my childhood cat, Emmett, and I feel like there’s some of that energy in Rosenberg.

Emmett was like a cat dog. He was waiting for me at the door every day, following me around all the time like a dog does. We were very close, and Rosenberg has some of that too—in certain ways he’s shy and reserved when he meets somebody. Part of that’s catlike. In other ways, he’s very much a dog in how he wants to go everywhere with us and he gets wild and rambunctious in the way that he plays and functions.

But he’s a pensive guy, and he does have some anxiety like I do—it’s another part of our bond. And to me, the way we’re alike emotionally—we can both be very introspective and also very outgoing in situations—to me our personalities are more alike from a non-physical perspective than they are in how much everyone says we look like each other.